Shoulder flexion is this big bad word that barely makes sense when we are standing on our feet - and therefore, with so many things to think of when we are upside down, including our survival, becomes incomprehensible once our feet are in the air.

However, it is by far the most important movement pattern to grasp in your first year of handbalancing. Let’s see why and break it down step by step.

The mechanics of a handstand

One does not need to be an expert in biomechanics to understand that if you were to move your pelvis and your torso away from your feet, as you stand up, you would fall out of balance. In fancy terms we would refer to those as your centre of mass and your base of support.

To balance still on our feet with as much ease as possible, we need to keep our pelvis over our feet.

To balance on our hands, we need to keep our pelvis over our hands*.

(*at least in the vast majority of handstand shapes and certainly in the totality of handstand beginner variations).

Shoulder flexion

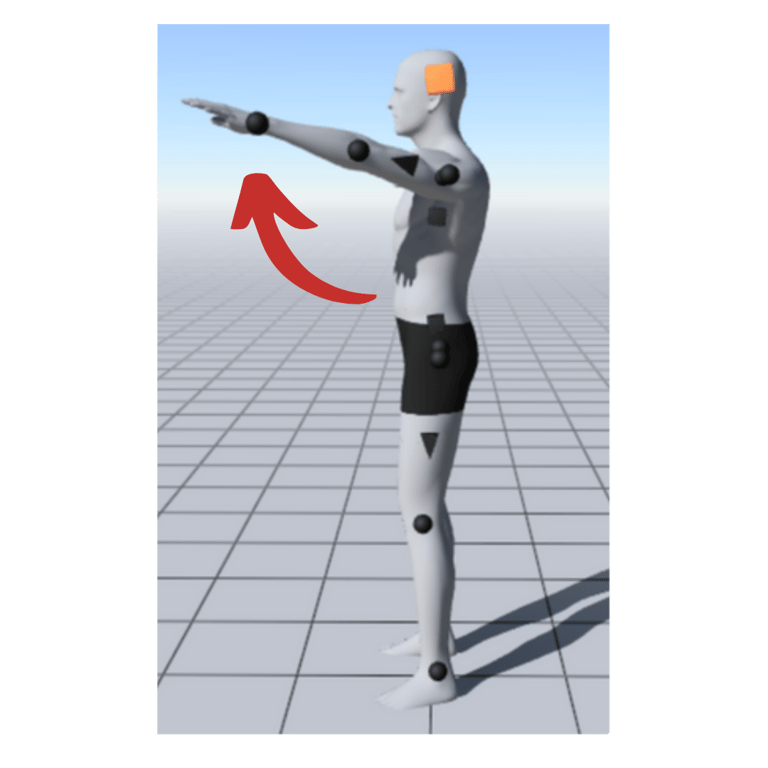

Shoulder flexion is what you do when you bring your arms overhead. If you are not too much into anatomy, this may sound counterintuitive, and you may be tempted to call that an extension or something.

Doesn’t really matter, call it whatever you want. What matters to us is that you can perform it in a closed-chain context, that is, with your hands glued to the floor.

There is one thing you know for sure about handstands: your hands are on the floor, bearing all your weight.

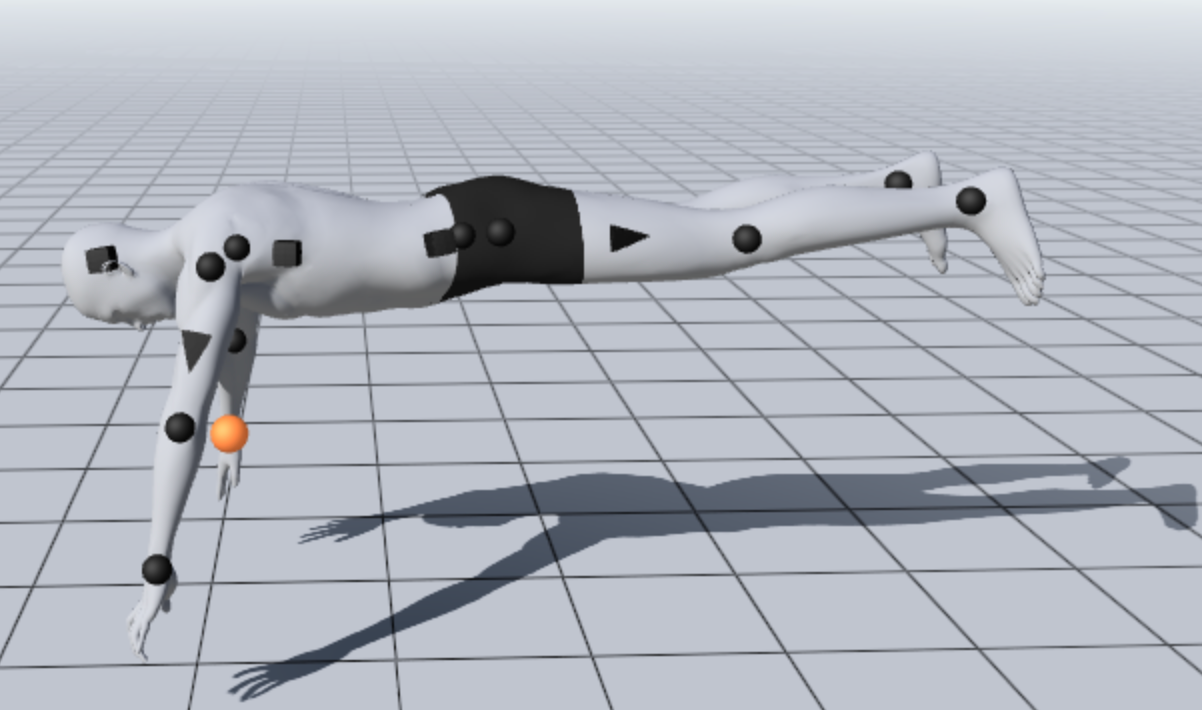

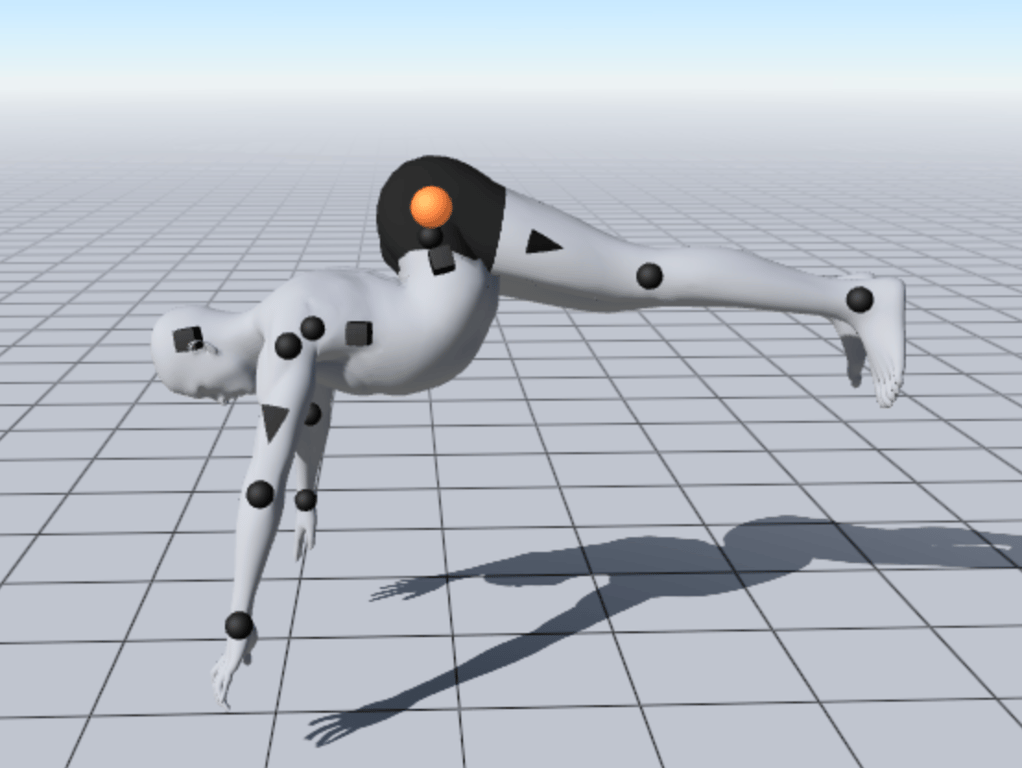

If we flip our character above, with the same body shape, so that it had their hands on the floor, we would end up with a weird push-up position, at best:

Duh. Obvious.

Now, you know, intuitively, that the pelvis and the legs have to be overhead.

But realise that if we only move the joints related to the former or the latter, we would still not have a handstand.

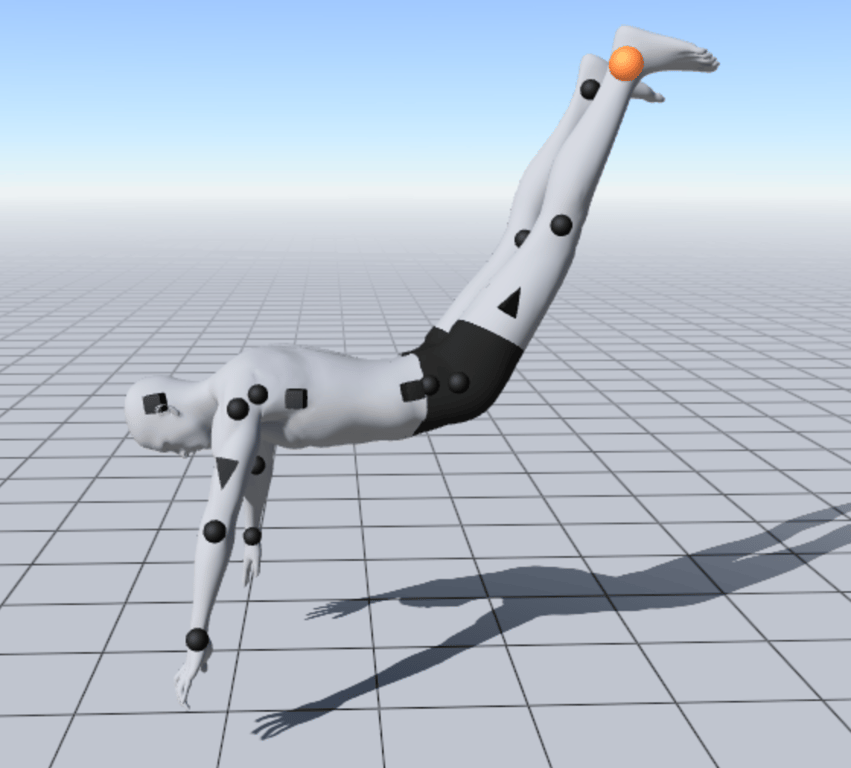

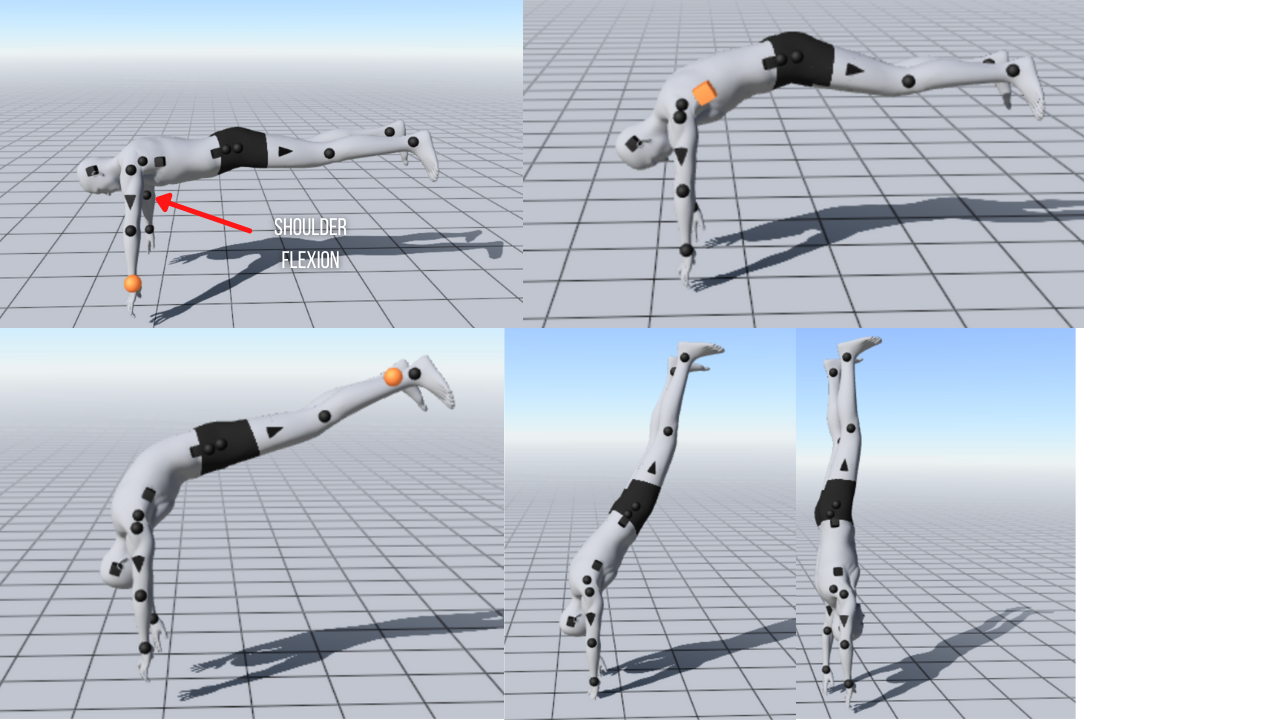

Instead, if we didn’t change anything to the rest of the body, but performed shoulder flexion, here is what would happen:

Tadaam.

Not good enough for cirque du soleil.

But a handstand nonetheless.

Looking at this progression, you can realise that:

→ as we perform shoulder flexion, the angle between the arms and the torso increases, or opens. That is why I will refer to this in class as “shoulder opening”. This is also why people who don’t have the mobility to bring their arms at a 180 degree angle at the shoulders will sometimes be referred to as “closed shoulders”.

But don’t let the Internet bully you. There is a fix for that.

→ Shoulder flexion is paramount to aligning our centre of mass over our hands or, in a less pompous fashion, to bringing our butt over our hands. Much more so that a pelvic tilt, an extended leg or a pointed toe.

→ Shoulder flexion with our arms in the air (what we call an open-chain context) feels easy. In a close-chain context (hands glued on the floor), not so much.

→ As we perform shoulder flexion, a host of other movements seem to happen consequently in our bodies:

- the head goes in

- our butt travels out

- our chest moves in

Those are all relevant cues when you are trying to tap into that movement pattern.

Let me rephrase that: once you are upside down, screaming “I am going to flex my shoulders now” hardly does the trick because, again, it’s a weird one. But bringing our chest in, ie towards the wall in you are holding yourself chest to the wall, may make more sense.

Try to think about what is happening in your own body when you do this movement.

How would you describe that to a 3 year old? Where is the sensation located?

Whatever you find, add this to your thesaurus: this is the cue, your cue, that I want you to summon back to consciousness whenever you hear “open your shoulders”, whether on the floor, back to the wall, chest to the wall or freestanding.

One last caveat

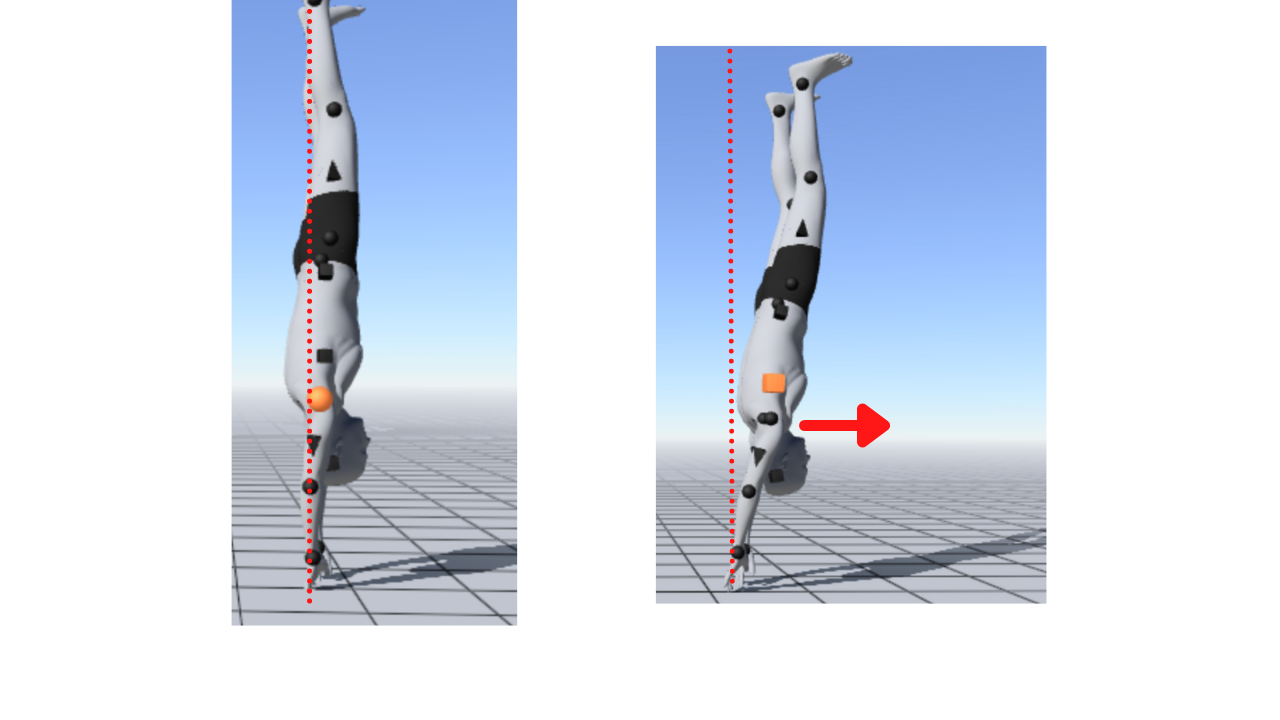

Shoulder flexion works great, IF it doesn’t happen at the expense of what precedes it in our handstands, namely: the stacking of the first axis.

Your hands are stuck on the floor: they are going nowhere.

Your shoulders though... may be tempted to lean forwards or, god forbid, backwards, as you perform shoulder flexion. This is natural, but will lead to the following

The shoulders come out of axis, and so does the pelvis.

Good luck saving that.