From 1st stack to 1st stacks

On your way to your first 5 seconds freestanding, there is only one thing that matters to me when it comes to your shoulders:

Bring them forward enough.

We didn’t care how far forward, as long as you didn’t keep them over the wrists or, worse, before that wrist line.

This position, called hollowback, is the Bane of your existence at first.

If you engage with it before you have a solid 30 seconds freestanding, you are shooting yourself in the foot, and that’s why you may have heard me say to you “more forward, more forward, more forward”.

Great… but for the following couple of reasons, it is now time to nuance the 1st stack and distinguish different subvariations with small differences and huge implications.

1) Kicking-up consistency. If the shoulders keep landing in different positions every time you kick-up, you keep changing the rules of the handstand game you’re trying to play. Remember your kick-up lasagna? Momentum, alignment and tension need to become more systematic. A chaotic kick-up leaves little room for balance.

2) Undershooting attempts. Your shoulders flex, a little or a lot, when you kick-up. As you know from the good aul’ days of Good Dogs, Bad Dogs, we have a tendency to change the first stack when we open the shoulders. This can result in consistent hollowbacking, itself resulting in a lot of undershot kick-ups.

3) Overshooting attempts. If the shoulders lean too far forward and enter the planched position, you do not want to achieve a functional alignment with your feet. In other words, planched shoulder and overshot legs or pelvis do not co-exist well. A lot of planchers and students with flexible wrists tend to do this. Their kick-up is too forward, not upward enough.

4) Loss of balance. If the shoulders move too much, as tool of macro-correction or out of lack of awareness, once you have caught balance, you will quickly fall. It’d be similar to moving your legs frantically overhead before even feeling stable. Doable but super hard. A stable shoulder position offers a stable base of support for your handstand. This also ensures your fingers learn to do their job without the shoulders overshadowing them.

Who should work on this?

At the blue belt level, basically everyone. You will need that level of refinement to address the nuances of the pikes.

But a good chunk of students at the yellow (commitment) and green (duration) belt levels will benefit from addressing this earlier. They fit the following profiles (are you one of them?)

Planchers & wrist contorsionists

In handstand, when you go a bit too far forward with your shoulders, you enter the realm of planching. You planche when your shoulder position allows you to use upper body strength to compensate for an alignment that otherwise would not be held. We have called this kind of alignment - dysfunctional.

Some planche by default because they’re strong. It’d be rude to not do it, since it tremendously help their balance, so in my book we embrace it first and we then proceed to teach their bodies how to rely less on brute force and more of subtle positioning.

Others planche without having the strength to support it: they kick-up, the shoulders lean forward a hell of a lot, but they don’t have the upper body strength required to make do and balance with that position. At play: their very flexible wrists, which give in as they push their way forward. This affects their ability to kick-up high enough (we often see a phase of not reaching the wall for this profile), at and without the wall.

For both types of people, “going forward with your shoulders” is not precise enough. Aiming for a vague first stack enables them in their planching habits. We need to draw the line between an acceptable first stack, and the planche.

Gamophobics

Which seems to be the name for people afraid of commitment. A joke of course, this seems to be in the context of relationships, but you get the point.

Handstands, when it comes to alignment, are about committing forward, far enough.

This is where the mental aspect of the practice lies.

Conquering our fears.

Trusting our body.

Our body will design a myriad of clever ways to hijack our attempts at committing too soon.

One recurring way to do so is to subconsciously misalign your shoulders, ensuring they don’t go where they belong: past the wrist line.

This leads you to undershooting, again and again. And, because it happens below your awareness threshold, you end up working on and trying to fix other, less pressing, elements, without addressing the root cause of the problem.

For this profile, aiming far enough with the shoulders is the name of the game.

Dancers

Knowing what to do in handstands in general, and in the world of alignment in particular, is one thing. Getting to perform it every.single.time is another. Blame the mind-body connection.

When it comes to the shoulder - wrist alignment, some students will happily land in a different position every single time they kick-up. Before the wrist line, past the wrist line, planched… This makes the whole game much more complicated, because each alignment has dramatic ripple effects on the way the rest of the body should be aligned, and how we experience balance in our hands.

If this is you, you keep changing the variables of your handstand at every kick-up, making consistency extremely hard to achieve. This usually translates into an inconsistent kick-up at the wall or inconsistent balance in your freestanding kick-ups.

For them, the mission is to be more precise in where the first stack is and how moving around that position involves both weight transfers and changes of the hand position that need to be acknowledges to limit the amount of dancing and increase stabilisation.

Injured addicts

You have sustained an injury, at the shoulder, elbow or wrist level. Putting weight on your hands hurts, sometimes, in some position. But not always. And you have a serious addiction (you wouldn’t still be reading if you didn’t…), so you keep practicing, against the sound advice of your doctor and the concerns of your coach.

Fine (no, not fine!), if handstands do have a place in your rehab program, you better clearly identify the positions that hurts.

In many (not all ) cases, the more wrist extension, the greater the hurt.

In light of what we said: we want to refrain from planching, or getting near planching, as this increases the load on the wrists and shoulders.

In that scenario, aiming for a first stack that is just after vertical but certainly not too far forward would be advisable.

Arrows

Intermediate students who develop a fascination for the straight line will start bothering with details such as - protraction, super duper pointed toes, removing the back arch, PPT, and more.

At that stage, we’re sculpting a solid handstand into a work of art, heading for the museum. Meaning - you need a rock solid handstand first.

In uncovering your best line ever, we may to yank the first stack back to something more perpendicular (going full circle with how we started this article, the very thing that beginners and improvers should NOT do), and learn to balance there (it’s more difficult).

At that stage: it’s a good problem to have.

First stacks 2.0

Now that you know your profile, let’s see how we can more precise to guide your practice.

For this, we will have to deconstruct our now-too-vague 1st stack into a handful of positions:

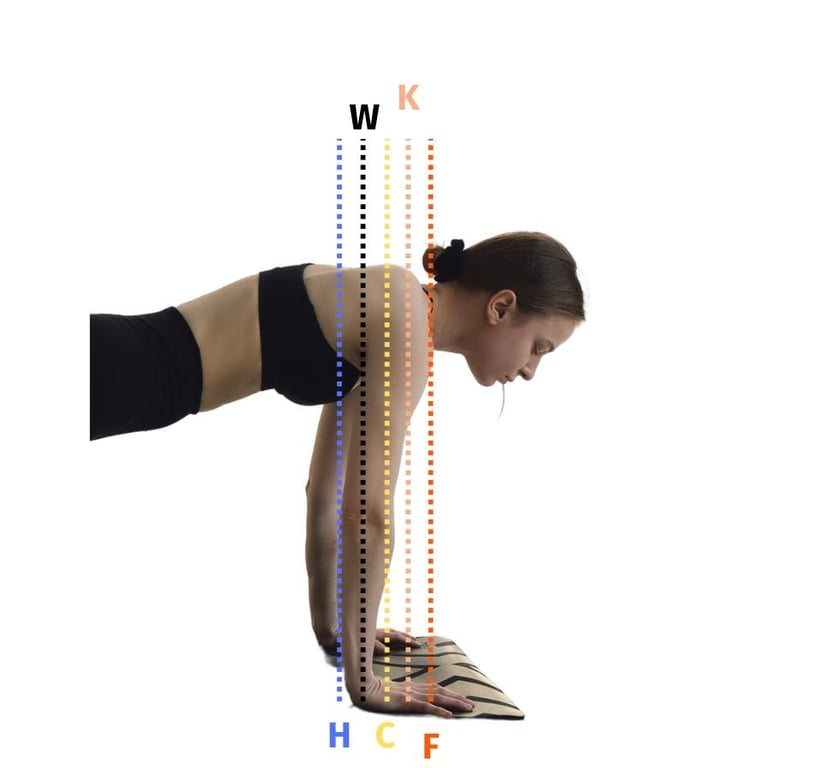

Point H (for Hollowback): your shoulders are before the wrist, perpendicular line

Point W (for Wrists): your shoulders are over the wrist line. The shoulder - wrist line is perpendicular to the floor.

Point C (for Center): your shoulders are over the centre of the hands

Point K (for Knuckles): your shoulders are over the 1st knuckles.

Point F (for Fingers): your shoulders are over the fingers - you are now planching.

W, C and K are all distinctions within our good aul’ 1st stack.

Spend some time recognising their subtle differences, going from one to the other while tethered to the wall.

Interestingly, balancing a handstand in each of these positions will feel different and impose different demands.

The more forward, the more shoulder-strength driven

The more backward, the more alignment-driven

Application

Your plan of action goes as follows:

Planchers and contortionists → aim for W or C. Emphasis on getting there from the kick-up (instead of stabilising first and then moving there)

Gamophobics → aim for K. Yes you hate it.

Dancers → aim for C or K. Learn to balance whilst staying in the chosen spot.

Injured addicts → rest. Ok I said it. Otherwise, and if proven safe, W. Oh that won’t be easy to balance.

Arrows → aim for W. Kicking up into it, balancing in it.

Blue Belts and above: master them all. Careful with the extremes (F and H) though.